This company was (rightly) very proud of its diversity record; it was an organisational powerhouse, with a strong culture, working hard on equity and inclusion, with impressive statistics around gender, ethnicity and under-represented groups to back it all up.

However, apart from it being the right thing to do for so many reasons, they weren’t seeing the anticipated uplift in problem solving, innovation and engagement that they were expecting.

It seemed like the diversity dividend wasn’t delivering.

So I took a look and noticed something interesting: the rigour of the recruitment and selection process, the absolute clarity of the career path development and the rigidity of the project team selection criteria (all of which were about intellectual excellence) were actually working against them.

This company was unintentionally creating a cognitive monoculture.

It was an intellectual racehorse – very fast in one direction but ill-equipped for the twists and turns and heavy loads of a rapidly shifting business context. So we had to start thinking about how to broaden the cognitive landscape; allow for some fresh thinking, encourage novel approaches and get used to some uncomfortable conversations.

“Getting cognitive diversity right is probably the most important thing for organisations in the coming 25 years, because the world is changing fast. Having different lenses on multi-dimensional problems is a hugely important way to come up with winning strategies, great predictions, and excellent innovations.”

Matthew Syed (journalist and broadcaster)

This blog covers a significant (but not exhaustive) overview of this important and often overlooked aspect of diversity in high performing teams. In it, you can find out more about the following:

- Some definitions of what cognitive diversity is, and how it is distinct from neurodiversity

- The benefits of cultivating cognitive diversity in your teams

- The very real danger of groupthink

- Some of the challenges of working in a cognitively diverse team

- There’s a Field Guide to help you recognise different types of cognitive cultures

- And at the very end is a downloadable version of the Cognitive Cultures Field Guide.

Some definitions

Before we get into what that cognitive diversity looks like, maybe some definitions are needed.

Cognitive Diversity: a useful working definition might be: “the range of different ways individuals perceive, think, and approach problem-solving tasks.”

It encompasses variations in cognitive styles, perspectives, information processing methods, and problem-solving strategies among members of a group or team. Unlike more familiar diversity dimensions such as race or gender, cognitive diversity focuses on the unique cognitive strengths, preferences, and skills that individuals bring to the table, leading to a rich tapestry of insights, ideas, and approaches within a collaborative setting. It is distinct from neurodiversity, which has a more specific meaning.

Neurodiversity: a concept that recognises and celebrates the natural variation in human neurology. It suggests that neurological differences, such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other conditions, are variations of the human brain rather than deficits or disorders. This perspective challenges the notion that there is a “normal” or “typical” brain and instead advocates for acceptance and appreciation of diverse ways of thinking, learning, and experiencing the world.

In the context of this blog, I am focussing primarily on the former, rather than the latter, but there is clearly an overlap in terms of being more open to different ways of problem-solving, framing ideas etc.

“The electric light did not come from the continuous improvement of candles”

Oren Harari, business professor, University of San Francisco

What are the benefits of Cognitive Diversity?

When it comes to encouraging cognitive diversity in our teams, there are four “big ticket” reasons for making it happen: creativity, problem-solving, decision-making and change.

And these four areas matter more than ever – it is our ability to create our way through the problems we face and make consistently robust decisions in the face of so much change, that is already key to how teams thrive:

- Increased Creativity and Innovation: teams composed of individuals with diverse thinking processes tend to generate a wider range of ideas about how to solve problems. And it is this volume and variety of ideas that matters. Mono-cognitive teams often stop at the “first feasible solution” and then spend their time refining a mediocre idea rather than pushing through and looking for more. The adrenaline rush of moving to solution-ising is too powerful and we are already into implementation before we have even properly considered what else it could be.

- Improved Problem-Solving Abilities: different perspectives enable teams to analyse problems from various angles, leading to more comprehensive and effective solutions. Anybody who has done a crossword, or a tricky puzzle of any kind, knows that sometimes we get stuck. We can’t see a way through, we take a break, come back and the answer is suddenly glaringly obvious. Sometimes, the route towards a solution is not found by pushing harder but by seeing with a fresh pair of eyes.

- Enhanced Decision Making: being exposed to alternative ideas and fresh approaches encourages critical thinking and reduces the risk of groupthink. As Walter Lippmann wrote, “when all think alike, no one is thinking” and so we need to become much more comfortable with the constructive conflict of testing ideas and assumptions in a fully rounded way. In a context where we need to adapt quickly, the rigour and discipline of having recognisable and valued space for proper exploration leads to more robust and viable decisions.

- Better Adaptation to Change: a team that values diverse thinking processes is already setting itself up to be successful in navigating change. It is building a habit for challenge and a curiosity about alternatives in the smaller things, which make it more capable when it comes to the larger ones. It is a team that is not only likely to successfully react to change and be more resilient, but it is also likely to have anticipated the need and acted before it was required to.

The Dangers of Groupthink

The most famous reference to groupthink is undoubtedly George Orwell’s book, 1984, but as a psychological reality, it is already with us; a dangerous companion to cognitive monocultures. Whether it is the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 or the collapse of Swissair in 2002, the very real consequences of Groupthink are laid out before us.

In 1971 the psychologist, Irving Janis identified eight characteristics of groupthink; so these are the things to look out for:

- An illusion of invulnerability; it is assumed that any decision will be successful

- Inherent morality; assuming that any decision will be the right one, taken for the right reasons

- Collective rationalisation; dissenting opinions can be rationalised and therefore ignored

- Out-group stereotypes; alternative opinions are seen as deliberately contrary and oppositional

- Self-censorship; team members feel unable to express their true opinions

- An illusion of unanimity; everyone in the group is assumed to agree and silence is taken to be assent

- Direct pressure; dissenters need to comply, agree and avoid conflict

- Self-appointed mindguards; individuals who protect the group by imposing that direct pressure or omit information that contradicts the central tenet.

“Who controls the past controls the future.Who controls the present controls the past. War is peace. Freedom is slavery.”

George Orwell: 1984

What are the challenges of Cognitive Diversity?

Whilst the risks of Groupthink and a cognitive monoculture are very real, the actual delivery of a cognitively diverse team is not without its challenges too. It isn’t always an easy place to be; it can be frustrating and confusing. It needs some sophistication in the team as a whole and significant leadership to navigate successfully.

These are just some of the hidden rocks where teams can run aground:

- Communication Barriers: different thinking styles lead to misunderstandings about intention, purpose or process. Leaders need to work hard to address communication breakdowns and ensure that teams have appropriate Shared Mental Models [LINK] and a shared vocabulary.

- Conflict and Tension: diverse perspectives can lead to frustrations, tension and conflicts where intentions are not clear. Individual team members need to be “conflict confident”; understanding how to de-escalate, reframe, summarise and clarify without attempting to avoid or minimise the very real need for disagreement and exploration of ideas.

- Difficulty in Decision Making: this might seem to contradict the point above about enhanced decision making but actually the difficulty is not in the quality of the decision but in the time and effort it takes to get there. To fully explore, to remain curious, to be challenged is exhausting and it takes energy; it’s so much easier to go with the easy option. Building a workable consensus, without lapsing into Groupthink will take longer in teams with cognitive diversity, but the pay off makes it worth the additional time and effort.

- Fixed Mindset: some team members may be resistant to embracing diverse perspectives, preferring familiar approaches to problem-solving. It feels faster (at least in the short term) and take less cognitive load; go with the familiar, improve on what we have done before, move quickly are all hallmarks of a reluctance to engage.

What do different cognitive team cultures look like?

Here is a quick Field Guide to Cognitive Cultures in Teams. It briefly sets out nine different ways that cognition processes in teams can be characterised:

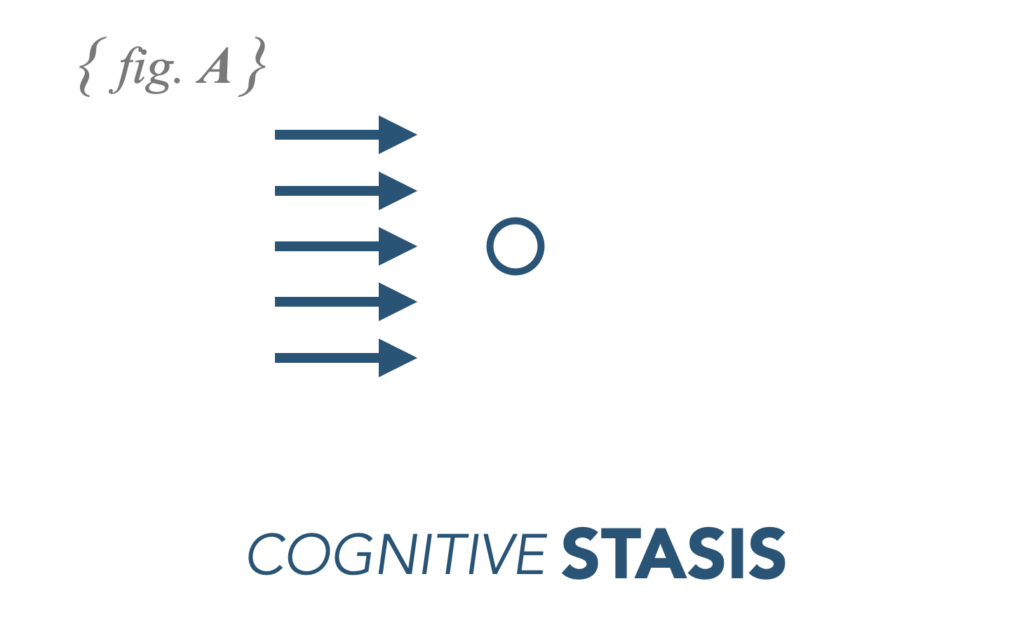

fig. A – Cognitive Stasis

Most commonly observed in mono-cognitive environments, where there is little evidence of diverse thinking and a heavy expectation to solve tasks in a particular way. Effective in the short term, within prescribed conditions, but this team is likely to stagnate over time, particularly if faced with a rapidly shifting context.

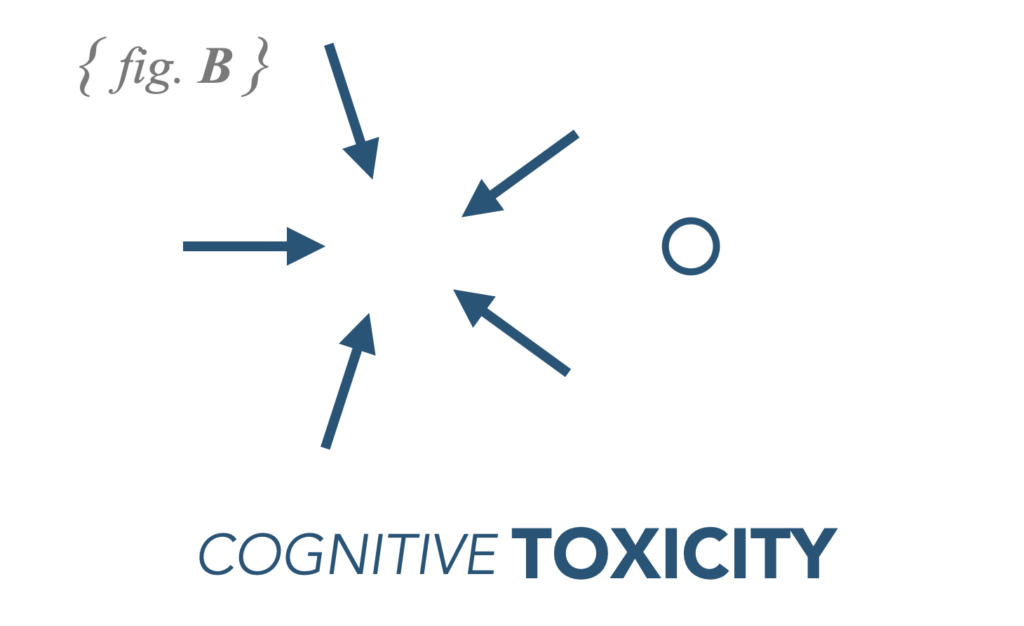

fig. B – Cognitive Toxicity

A frequently observed phenomenon, particularly in highly intellectual or technically competitive environments. Characteristics include ignoring the problem completely and preferring to challenge the competency and approaches of colleagues.

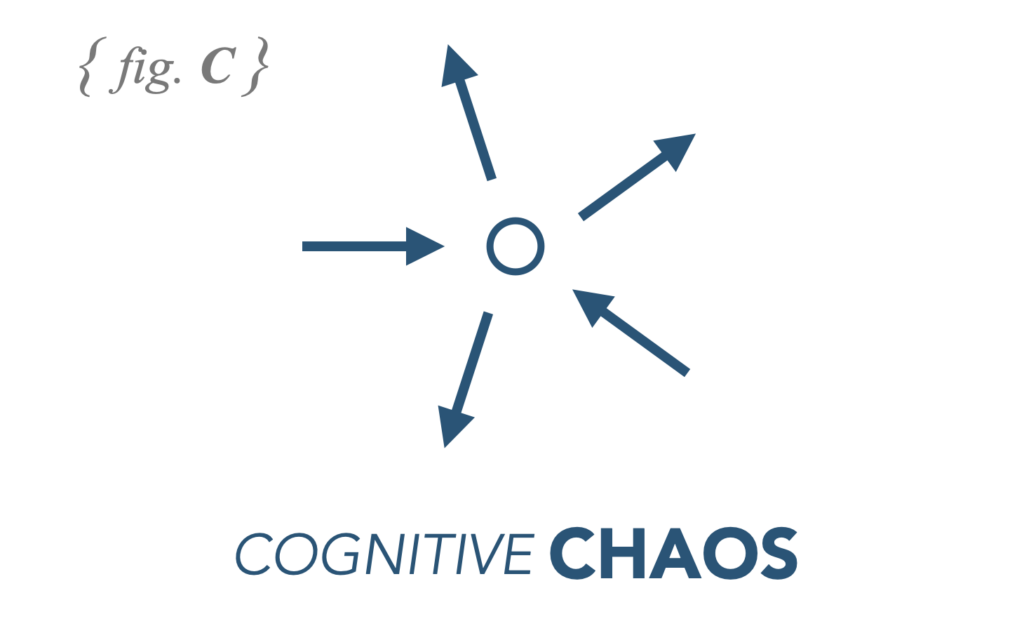

fig. C – Cognitive Chaos

This culture thrives in environments of ineffective or absent leadership, where team members display a lack of clarity about outcomes. There are ill-defined processes that impede rather than help, and colleagues can dip in and out of the cognitive process based on their own interests and time constraints.

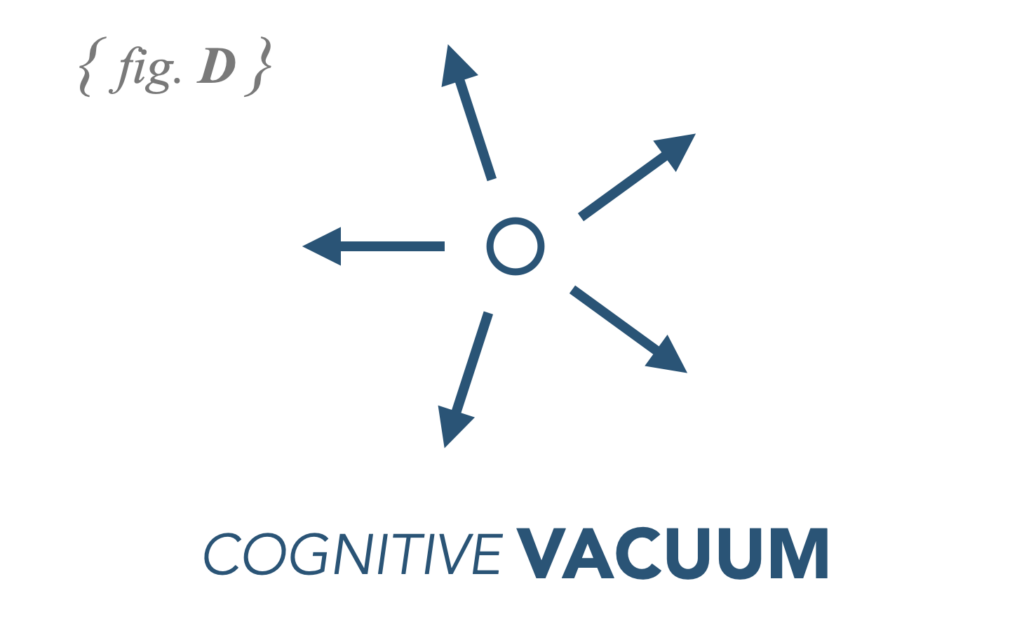

fig. D – Cognitive Vacuum

This case is easily recognised because nobody cares about the problem or can articulate what challenge they are trying to solve. Often a symptom of disengagement or frustration, this behaviour has deep roots and requires serious leadership care if discovered.

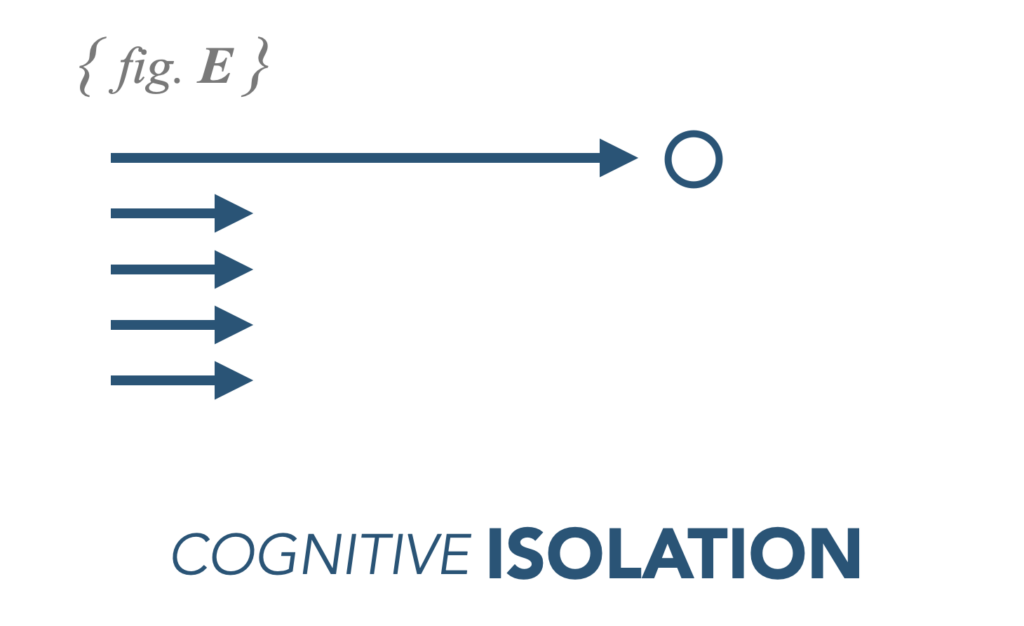

fig. E – Cognitive Isolation

Often seen where there are high potential individuals or perhaps a broader culture of endemic learned helplessness, this cognitive pattern is an easy ticket for the wider team. Default behaviours here are about “leaving it to the superstar” or a general sense of being left behind and waiting for somebody else to solve the problem.

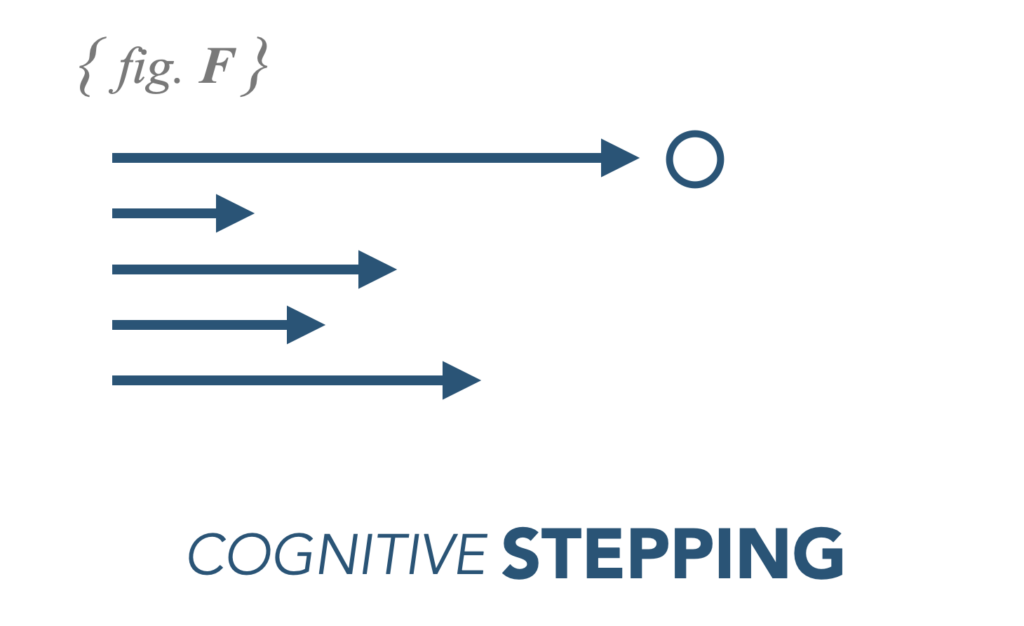

fig. F – Cognitive Stepping

A broadly positive culture of cognitive processing where team members are aligned on the problem to be solved. What distinguishes this variant is the concept of “temporal diversity”. Team members relate more readily to specific time frames (short, medium and long term thinking) which has a positive impact on strategy, implementation, planning horizons, and a sense of urgency.

Teams with balanced “temporal cognition” are up to 15% more likely to generate innovative solutions and adapt well to rapidly changing circumstances.

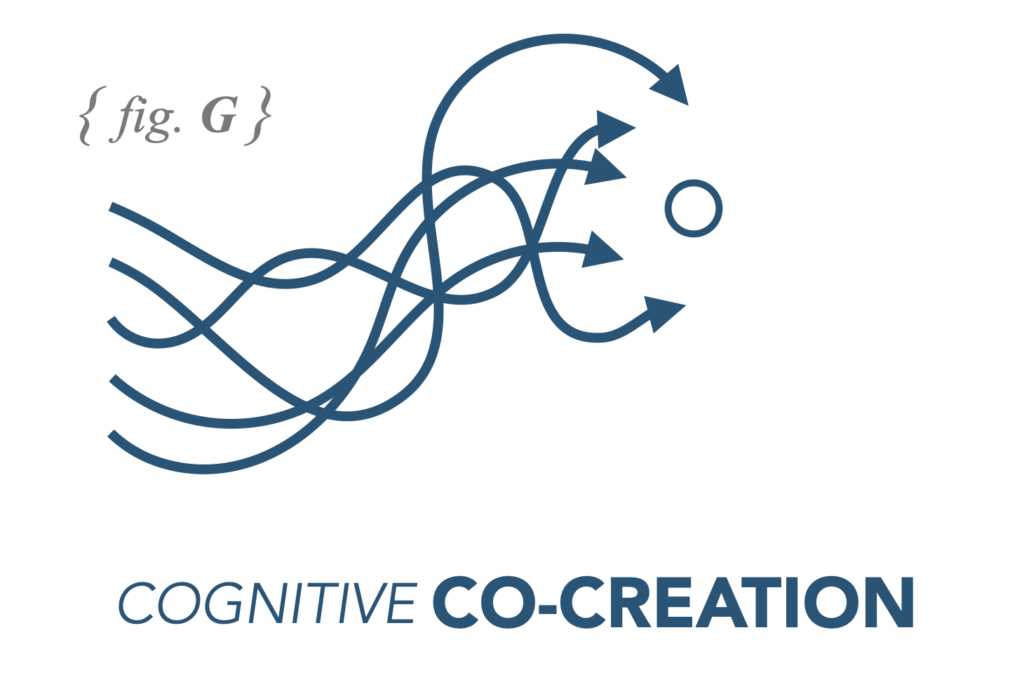

fig. G – Cognitive Co-Creation

This environment is a high energy, challenging, and interdependent culture of problem solving. Highly tolerant of debate and exploration, this culture can often be confused with “cognitive chaos” except in its tenacious focus on outcomes. It needs a clear and supportive leadership environment to thrive and benefits from frequent external inputs.

Strong task interdependence and supportive coordination mechanisms can lead to 25% improvement in performance outcomes.

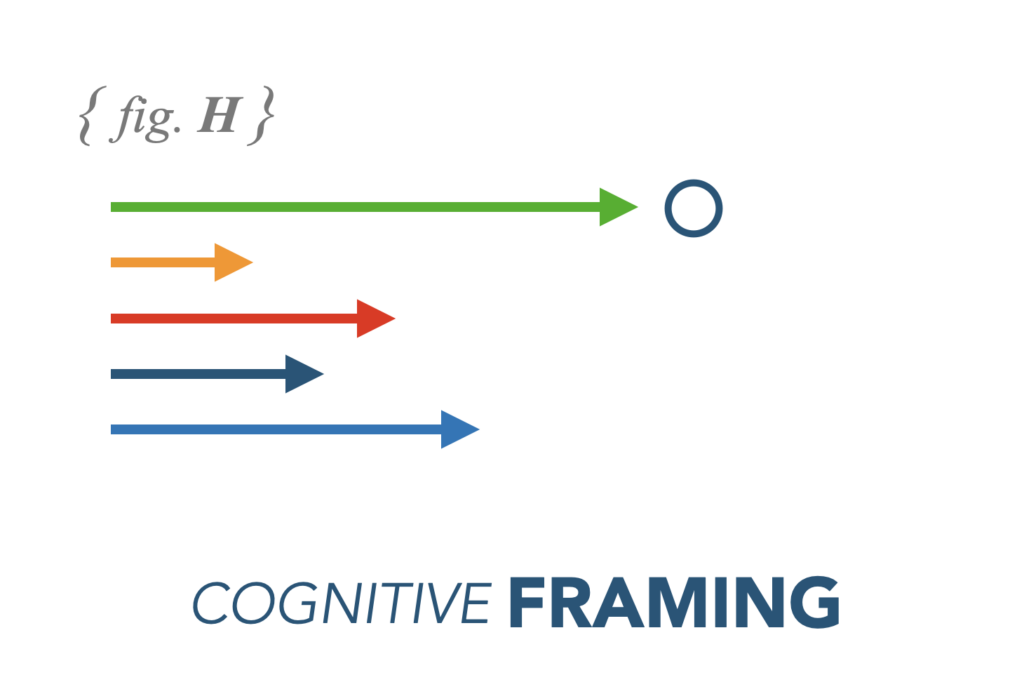

fig. H – Cognitive Framing

This is a rare variant of “cognitive stepping” and is rarely spotted in the wild. It combines the characteristics of “temporal diversity” but with some or all of these five distinct factors:

- Critical Thinking: making sense of complexity in a logical way

- Creative Thinking: generating new ideas, concepts, and insights

- Analytical Thinking: simplifying complex problems to understand the underlying structure

- Strategic Thinking: developing long-term plans and the steps needed to achieve them

- Metacognitive Thinking: reflecting on one’s own thoughts, knowledge, and cognitive processes

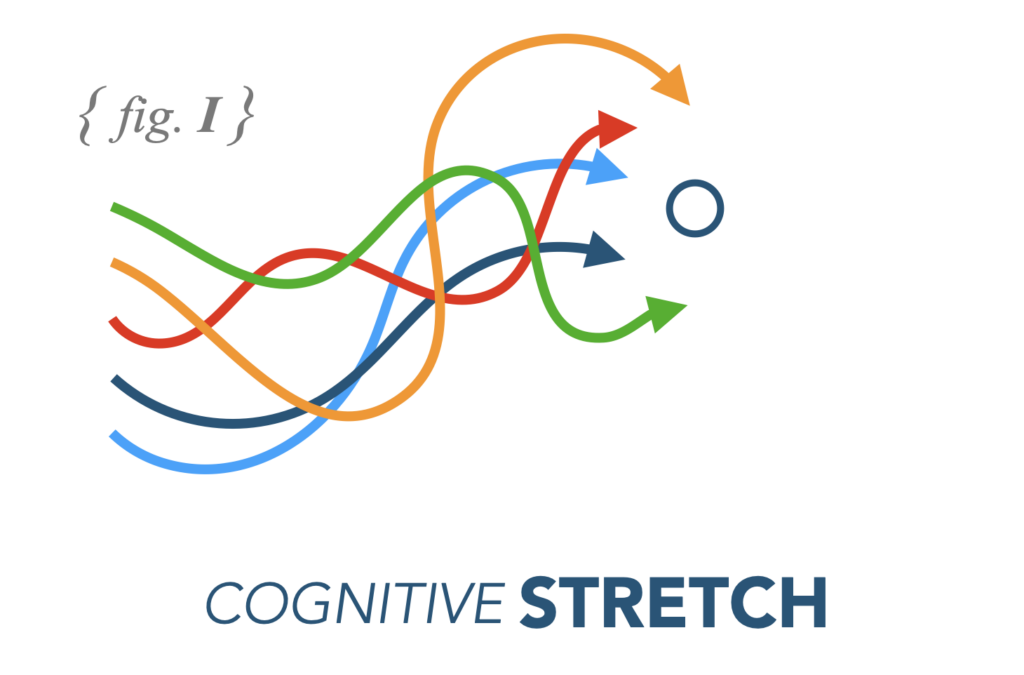

fig. I – Cognitive Stretch

The most rare of cognitive beasts, this variant is hard to capture and even harder to maintain. It doesn’t thrive in captivity and requires a very particular leadership effort. Combining forms of diversity that stem from lived experience and “temporal framing” through to “cognitive co-creation” and the five factors of “cognitive framing” this thinking process characterises the complex problem solving attitude of exceptional teams.

It is precious, delicate and powerful, needing diligent and agile leadership maintenance in order to flourish.

Cognitive Diversity may well be, in part, about getting more diverse people into your teams and organisations. But as with the consulting powerhouse, it’s no guarantee.

That particular company worked hard on addressing the issue, thinking more widely about recruitment and talent, and also by opening up the conversation; encouraging leaders and team members to challenge accepted practices and stretch their usual modes of thinking. Individuals began to explore fresh approaches and bring challenge because leaders with significant influence chose to create the “social permission” needed to make it happen.

If you want to foster a sustainable and powerful culture of creativity, innovation, and effective decision-making within your teams, then cognitive diversity is absolutely the place to start.

To help you on your way, here is a handy version of our Cognitive Cultures Field Guide.

When you want to find out more about the work we are doing around cognitive diversity with leaders and teams all over the world, do get in touch.

We are ready when you are.