What is it with questions?

When we are kids, we are great at asking them – “why is the sky blue?”, “how come fish can keep their eyes open under water?” – and then we seem to get progressively worse as we get older. We seem to get sucked into a culture of “knowing and advocating” rather than “asking and exploring”.

In a hectic landscape of meetings and projects, where agendas are packed and time is precious, effective communication is seen as the lynchpin of success, but all too often this is assumed to be about effectively setting out the argument or defending a position.

And yet, amidst the flurry of tasks and discussions, we overlook one powerful tool that can unlock everything: the art of asking well-crafted questions.

So what makes us so hesitant about asking great questions?

Maybe it’s the perception that being curious implies ignorance or naiveté? Or asking too many questions makes us feel vulnerable or concerned about being considered a troublemaker?

Perhaps.

“It may sound paradoxical, but strength comes from vulnerability. You have to ask the question to get the answer, even though asking the question means you didn’t know.”

Majid Kazmi, writer

But questions are not just avenues for seeking information; they’re catalysts for change, capable of shifting the culture and tone of any gathering. They are essential tools for any leader and in this post, I want to highlight the transformative impact of asking high-quality questions and the research-backed reasons why leaders need to embrace their power.

The keys elements are as follows:

- What can well crafted questions do?

- So what are the basic ground rules?

- How do you get what you need from open questions?

- How do we move beyond the obvious?

- Where can I find out more?

- What should I consider when thinking about high quality questions?

What can well crafted questions do?

Imagine two scenarios:

In the first, the weekly team meeting is dominated by a series of monologues; team members each set out their opinions and passionately advocate for a particular course of action. Questions, when they surface at all, are either:

- closed questions that generate simple yes, or no responses (“Is it true that we only made 3.5% margin in this quarter?”)

- disguised statements (“Wouldn’t you agree with me that we should be…?”)

- so long and complicated that they lose their power (“What I think we should be doing is blah, blah, blah… and what I would be interested in understanding is whether we should opt for A, B or C in Q3 using the D4SC protocol?”)

- or, at worst, are used as a weapon to undermine or trap others (“When you said to me last week that the margin was 3.5% and we now find ourselves here, what did you do wrong?”)

In the second scenario, members of the team carefully use open-ended questions to encourage participation, clarify and explore. The form and use of questions is significantly different:

- open questions invite specific enquiry (when, where and who give you data; whereas what gives you plans; how gives you behaviours and why elicits rationale.

- questions are short and clear (“what would you recommend?)

- potentially contentious questions are labelled with intention (“in order for me to better understand what is going on here, the question I want to ask is….”)

- questions build to fully explore (“what is it about this that really matters to you? If that is the case, what do you now need to let go of?)

- the questions balance a need for specific outcomes and clarity with space to imagine (what are the key actions as a consequence? what else could we be doing in this space?)

The difference lies not only in the questions asked but also in their intention and execution.

“The key to intelligence is asking questions.”

Richard Feynman (1918 – 1988), theoretical physicist

Well-crafted questions have the power to:

Inspire Critical Thinking: prompting individuals to reflect on their assumptions and perspectives; challenging questions stimulate critical thinking and deepen understanding.

Foster Creativity: questions that start with phrases like “what if” or “what else” or “what could we…” invite diverse viewpoints and unconventional ideas, fuelling creativity and innovation within teams.

Build Trust and Engagement: when we feel heard and valued, trust flourishes, and engagement soars. Thoughtful questions create safe spaces for open dialogue and authentic communication.

Understanding Perspectives: being genuinely curious about the context and decision-making process of somebody else helps us collaborate much more effectively.

So what are the basic ground rules?

In order to get off the ground with asking high quality questions (and receiving some valuable replies in return), it is probably worth being mindful of a few principles. It matters because crafting effective questions requires intentionality and practice, combined with an awareness of the context that you are creating, so perhaps start by considering the following:

Be Genuinely Curious: try to approach conversations with an open mind and a real desire to understand different perspectives. This is particularly hard when you are the expert in the room but your questions will help others see their assumptions or mistakes in a brighter light.

Practice Active Listening: pay close attention to responses you are getting back and ask follow-up questions to delve deeper into the conversation. To give you some context around this, the average time someone waits for an answer to a question in a meeting is only 0.7 – 1.4 seconds.

But if you increase the “think time” to just 3 seconds, you will get more accurate, considered answers, better engagement, and improved outcomes.

Summarise: every so often (maybe every 7- 10 minutes), just summarise what you understand so far. You don’t have to agree with anything but play back what you are hearing so you are demonstrating that you are listening and checking for any misunderstandings, assumptions or biases.

Create a Safe Space: foster an environment where individuals feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and ideas without fear of judgment, whether this is in one to one conversations or team meetings. And to be really clear, this doesn’t mean avoiding tough conversations – a psychologically safe space actually enables deeper and potentially more difficult conversations to happen well.

Using Closed Questions: these types of questions are not framed to encourage exploration; they are about getting to a commitment or a factual clarity. Which is why journalists and barristers love them so much (Is it true to say that you were involved in the decision? Will you be at the next meeting when we discuss this again? Do we have enough resources for this to happen?)

Closed questions definitely have their place but tend to be over-used in most meetings I observe, so maybe limit them to initial clarifications and final commitment gathering?

The scientific mind does not so much provide the right answers as ask the right questions.

Claude Levi-Strauss (1908 – 2009), anthropologist and ethnologist

How do you get what you need from open questions?

Unlike closed questions, open questions are all about exploration, data gathering and understanding motives. They take longer to answer (which is maybe why we don’t use them enough?) but tend to give us more context and content. Consider how to use them to get to specific types of information:

When? Who? Where?

Questions that start with any of these three words are going to be great for getting specific, relatively low level information about what happened or is going to happen. They are not very exploratory but will give you useful information about the plan.

What?

A question that starts with this one will encourage answers that focus on strategy, planning and the mechanics of getting stuff done: what did we do? what else needs to be done? what have we missed?

How?

Questions that start with “how” drive towards behaviour and problem solving. The difference is subtle but try it in a meeting and see what happens: how did we do? how do we need to do this? how could we have done even better?

Why?

Questions that start with “why” are powerful and dangerous in equal measure. “Why” gets us to root cause and motivation (why did it fall over? why does this matter to you?) but also to defensiveness and justifications. Think about the impact of this type of question from someone in power: why did you do it like that? why did it go so wrong? – you are more likely to trigger limbic flight, fight or freeze behaviours rather than get to any useful insights.

When in doubt about the impact that a “why” question might have on somebody, try re-framing it as a “how” or “what” question instead. It will get you to the same place but in a more constructive way.

Let me explain by using the examples above:

A WHY question might be: why did you do it like that?

The WHAT alternative would be: what was the basis of your initial decision?

A WHY question might be: why did it go so wrong?

The HOW alternative would be: how would you do it differently next time?

Do you see the difference? The questions feel less accusatory and more genuinely interested in understanding what went on or is going to happen in the future. Don’t get me wrong; there is definitely a big place for “why” questions but maybe focus them on inanimate objects: “why did the valve fail? why is the market shifting in that direction? and you are more likely to have successful open conversations.

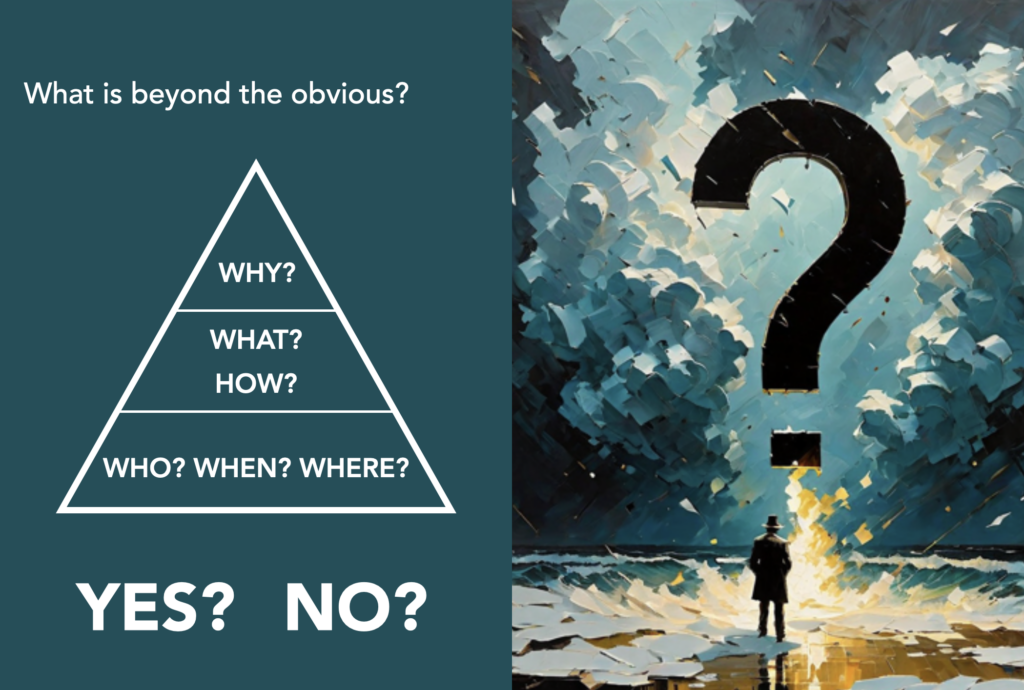

How do we move beyond the obvious?

The Germans have a great word: Grundsatzfragen. It describes the importance of fundamental principles and the questions that underpin the foundations of decision-making. In essence it embodies the idea of getting to the important questions. We don’t have an easy equivalent in english but I have always appreciated the idea of searching for the Grundsatzfragen.

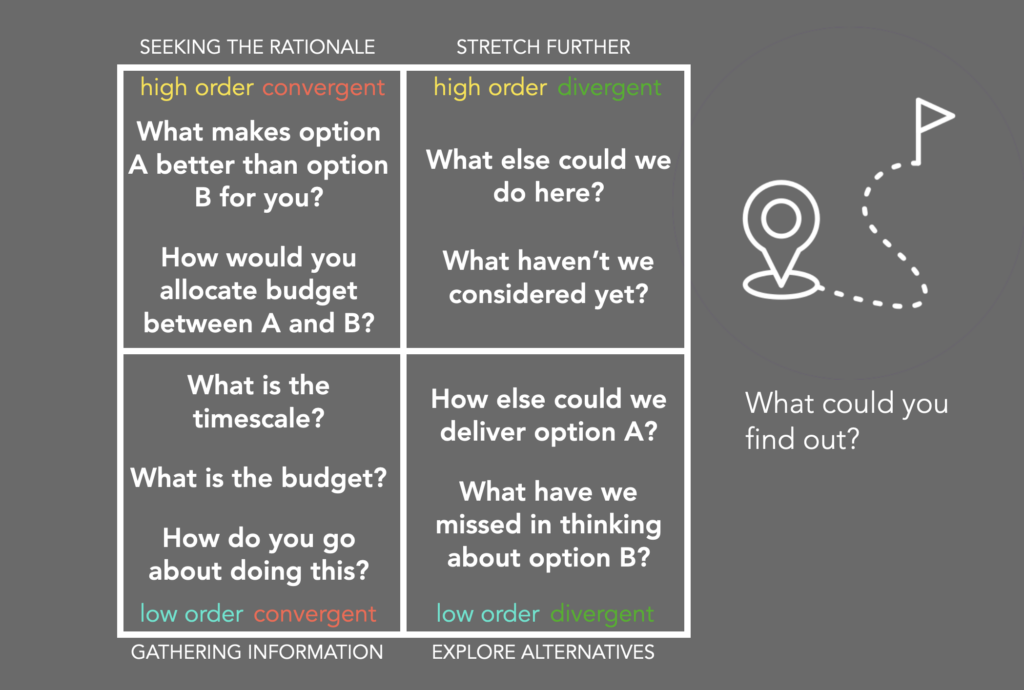

In order to get there, we can elevate this whole discipline of question-crafting in two oppositional modes:

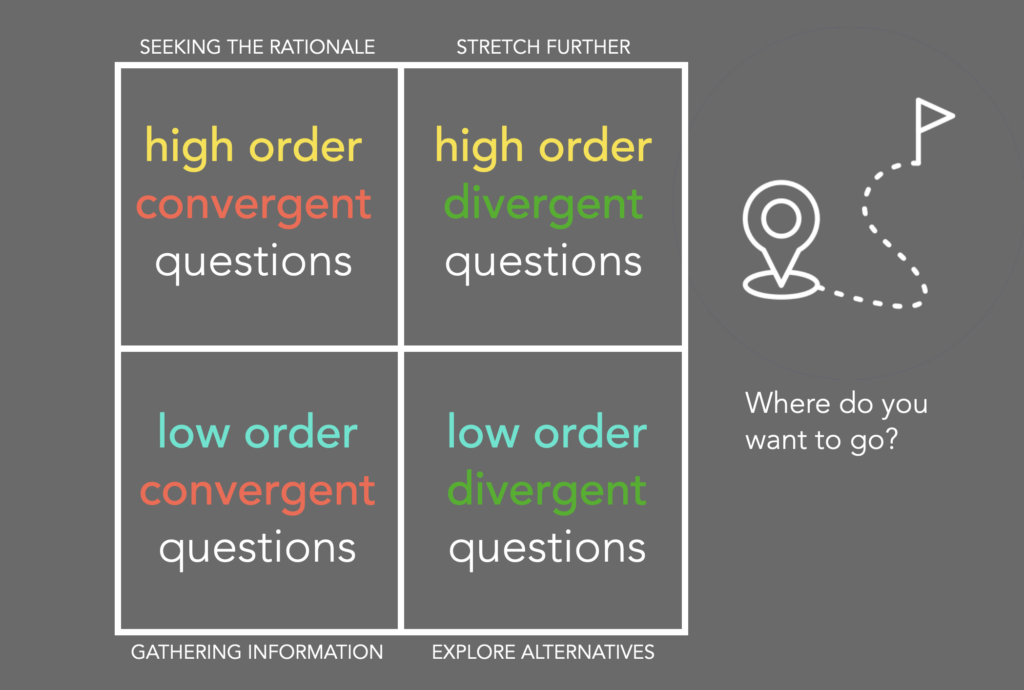

Convergent Questions versus Divergent Questions

The way we frame a question can take us in one of two directions; into a funnel of specifics or outwards into a world of exploration. This isn’t about one type being better than the other, it’s more about what is most appropriate or useful at any given moment.

If you want quick, focussed responses that yield actions and information, go with a convergent question (“What have you done about….?”) whereas if you want more reflection, go with something more divergent (“What did you learn from….?”).

Think of these as your OPERATIONAL questions.

Low Order Questions versus High Order Questions

Another way to approach question framing is to think of them as “ambition” questions; the difference being that low order questions are constructed to give you factual responses (“What did we produce last week….?”) whilst high order questions encourage context creation and are generally more ambitious (“What would make the biggest difference….?”).

Think of these as your STRATEGIC questions.

So far, so complicated. I get that. But when you combine these two modes together into a four box matrix something magical happens.

We create a route map for quality questions.

You now have structured choices about where you take the conversation: are we still gathering information (bottom left) or starting to get to the rationale (top left)? It might be that we need to explore alternatives, (bottom right) within the low order constraints that we have (improving on a existing product, for example) or we need to go for full on paradigm shift by stretching further (top right).

You are probably not going to use question types from all four boxes equally, but with the framework, you now make a conscious choice about how you want guide the conversation.

In studies, up to 85% of questions in meetings fit into the bottom left quadrant whilst only 5% of questions asked fit into the top two boxes combined. This data alone should tell you something about the quality of the dialogue in most business meetings.

The care and attention you put into the questions you ask has a significant impact on the quality of the dialogue. And this is a leadership act, whether you have positional power or not; challenging assumptions, opening up new ideas or clarifying areas of misunderstanding.

Where can I find out more?

Crafting hight quality questions to improve team and organisational effective is a huge topic, so here are some additional points of reference:

The Power of Inquiry by Edgar H. Schein – a focus on the importance of asking the right questions in organisational contexts.

The Art of Powerful Questions by Eric E. Vogt, Juanita Brown and David Isaacs – a short but insightful exploration of question structures

The Progress Principle by Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer – a more intensive read, which explores how small wins and meaningful work fuel creativity and productivity, highlighting the role of asking insightful questions.

Group Genius by Keith Sawyer – a more specific focus on how collaborative creativity works and the role of questioning in fostering innovation.

Leadership is Half the Story by Mark van Vugt and Anjana Ahuja – for an exploration of questions through the lens of evolutionary psychology, this book set out the significance of asking effective questions in leadership roles.

What should I consider when thinking about high quality questions?

If you are serious about accelerating your leadership presence with more impactful, useful questions, create these eight conditions for them to thrive:

- Structure – keep your questions short and clear. Then shut up and allow time for the question to sink in

- Framing – if the question could be perceived as contentious, label your intention (the reason why this matters to me is…) and use language and phrases that resonate with whoever you are asking

- Stepping – think about the purposeful build of your questions and how you navigate your way towards solutions, disclosure or fresh ideas

- Find the Balance – ask both convergent and divergent questions, high and low order, in an appropriate order and ratio to make it feel like a curious build

- Share of Voice – encourage responses from all; redirecting asked questions back to others

- Getting Deeper – use follow on questions and ask others to clarify, expand or support answers

- Encourage Think Time – pause for 3 to 5 seconds after asking a question for time to think. Do the same when asked a question

- A Curious Culture – a conversation with high quality questions shouldn’t feel like an interrogation; it is a considered sharing of ideas and opinions with a genuine curiosity and a desire to understand fresh perspectives. Expect and encourage quality questions from others too.

A culture of deliberate, high quality questions brings better outcomes. And it is definitely part of how you lead others.

If you would value more insights and ideas about how to go about it, please get in touch.

We are ready when you are.