A tale of two shipwrecks: leadership when the worst happens.

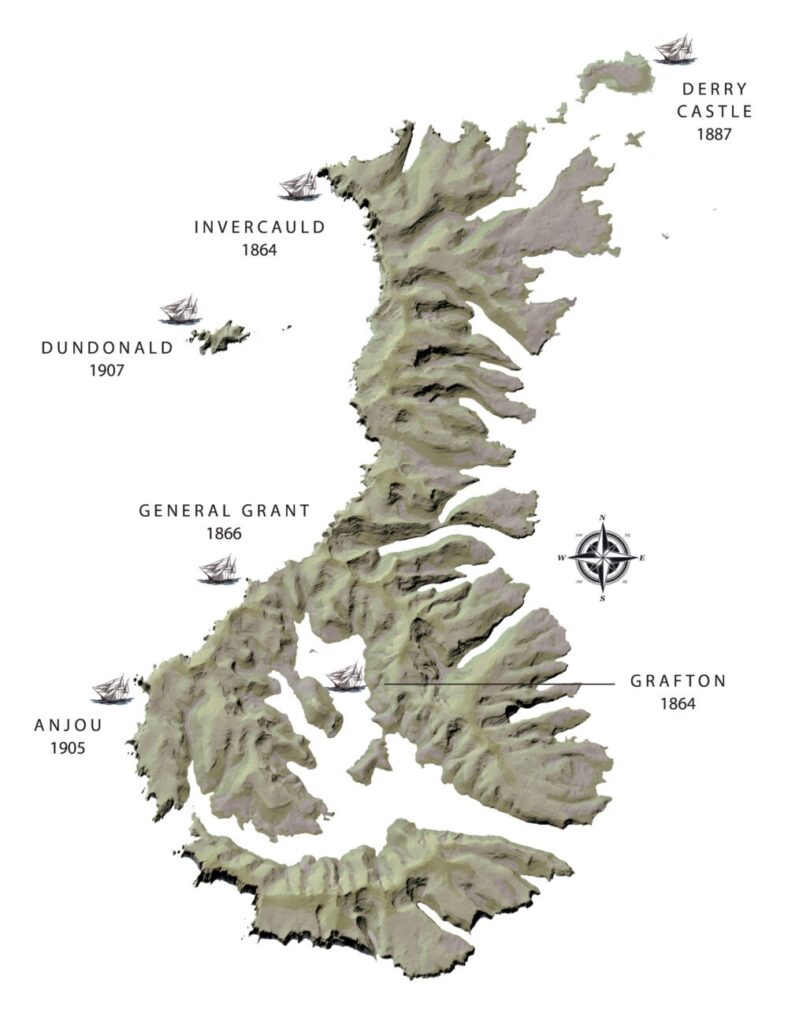

In 1864, two storm-ravaged ships were hurled onto the unforgiving rocks, top and bottom of the same island, twenty-five kilometres apart and five hundred freezing kilometres south of New Zealand.

The small crew of one of the ships built a shelter, hunted seals and eventually built a boat to sail back to safety. The other crew descended rapidly into fighting and cannibalism. Only three of them survived to be rescued.

What determined their very different outcomes?

Was it Collaborative Leadership?

Collaborative Leadership is a relatively modern concept but its central ideas might just have been key to why the more successful crew were able to escape.

The term itself was first coined in 1992 with the founding of the Institute for Collaborative Leadership in the USA. Its creation reflected increasing public sector and societal inter-connectedness and the growing expectation for organisations and leaders within them to collaborate more effectively.

“If a collaboration is to be effective, each party must recognise and respect the different culture of the other”

Rod Newing – Financial Times

At the time, it was radical concept, alien to most business leaders. It was (and perhaps still is) at odds with the traditional “command and control” leadership paradigm, where a team of people and a set of resources are there to be managed – and success is rewarded with more of both.

Successful collaborative leadership requires a whole new skill set that is attuned to the external context and the needs of the team and organisation; it challenges the value drain of the Leadership Loopholes, moving from authoritarian parent-child to mature, adult-adult relationships. For some, this flattening of the hierarchy is a fundamental threat to the order of things, requiring a re-defining of what it means to be a leader. But for those who can do it, particularly in times of rapid change, it harnesses the power of the whole, creating more resilient, adaptive and successful teams.

At the heart of collaborative leadership are six core components that the leader, the team and the wider organisation need to keep working on:

- A clear North Star – a crystal clear vision and purpose that is referred to continuously and shared by all; it is used to help clarify decisions, priorities and strategic pathways

- Valuing diverse perspectives – actively seeking out fresh, alternative views, critical insights and creative options; an expectation and encouragement of difference, seeking the best options, not settling for the usual

- Community bonding – building deep empathy, care and respect within the team and organisation; asking for help, offering help; being vulnerable and courageous in the pursuit of excellence

- Broad spectrum communication – listening and sharing, debating and exploring, seeking to understand; not getting ego-attached to specific ideas or ways of working

- Robust challenge – expect and invite robust challenge to test ideas and ways of working; collaboration is a balance of cooperation and assertiveness, so expect assumptions and long-held beliefs to be queried

- Solution-oriented – the focus is on successful delivery, with energy and resources aligned accordingly; failure is learning and blame is a waste of time; accountability and timely, accurate feedback drive performance.

In his book, “Collaborative Leadership: it’s good to talk,” Steven Wilson outlines four specific leadership characteristics that underpin these. It is up to the leader, or leaders, or the team as a whole, to consistently role model behaviours that reaffirm what matters:

- that the goals of the whole always come ahead of self-interest

- that decision-making is transparent, consistent and considered fair; accountability is clear and agreed

- that resources are a means by which to get things done; aim for a frictionless flow of resources to where they are needed most, regardless of where they start

- that decisions, processes, accountability and rewards are codified; rituals, routines and a clearly understood vocabulary bring shared clarity.

Collaborative Leadership is not easy. Done less well, it gets bogged down in endless meetings, compromised solutions and frustrating confusion. The desire for all to be heard, without clear decision-making strategies, results in bland, shapeless outcomes; robust challenge without a clear North Star descends into chaos and in-fighting.

Those who do it well recognise that it takes effort, courage and vulnerability; there is a maturity and confidence to collaborative leaders and the benefits for all concerned are massive – leaders intent on building communities of leaders.

A tale of two shipwrecks

Back in the icy, storm-battered South Pacific, it is early January 1864 and the five sailors aboard the small trading schooner, the Grafton, finally make it onto the remote southern shore of Auckland Island; an inhospitable rock that would be their home for the next 18 months.

The owner, Francois Raynal, his captain, Thomas Musgrave, and their small crew seemingly came to terms with their new reality remarkably quickly. They had soon built a shelter and shared their meagre resources equally. They devised rules of behaviour that were written in a bible and were read out unfailingly every Sunday.

It was a time of raw hunger, freezing temperatures and a visceral fear of what faced them but as Raynal wrote at the time:

“If habits of bitterness and animosity were once established amongst us, the consequences could not but be most disastrous: we stood so much in need of one another!”

Francois Raynal

After almost a year, they managed to construct a small furnace, made nails and remarkably, were able to build a boat in order to eventually escape their inhospitable island.

Under Musgrave’s elected guidance they came to understand their collective responsibility for leadership and teamwork in radically exposed circumstances, which ultimately proved to be their salvation.

By contrast, in May of that same year, nineteen crew from the merchant ship Invercauld swam ashore further north.

Their captain, George Dalgarno, was paralysed by fear and indecision, his senior crew continued to insist on hierarchy and servitude, whilst the rest were listless, scared and starving. It took only five days for the talk to turn to cannibalism:

“It was the boatswain who first made the suggestion that they should draw lots for which of them should be the first to die, in order to save the rest.”

Despite having the larger crew and the benefit of finding a ready-made, albeit abandoned shelter and plantation, the crew dwindled and declined into chaos and savagery. After twelve months, just three survived to be rescued.

So what made the difference?

From written accounts of the time, it seems that the crew of the Invercauld were in denial of their new context, clinging onto old world rules, with a blind and passive belief that others would rescue them, before descending into a grim spiral of survival. A lack of leadership, a failure to adapt to a new reality, a dismissal of expertise and alternative ideas; and a grim dynamic of power and self-survival.

The five crew of the Grafton, on the other hand, appear to have adapted quickly to their new reality, took responsibility for their shared survival, jettisoned social structures that were no longer relevant, recalibrated their behaviours and created supportive mechanisms aligned to a purpose. They shared the meagre resources that they had and they valued the skills of the whole group, eventually daring to plan their own rescue: “If men abandon us, let us save ourselves,” proclaimed Raynal. “Courage, then, and to work!”

Perhaps they also benefitted from being an optimally-sized group from the very start?

Research into group dynamics suggests that a team benefits from having seven diverse members, plus or minus two. Enough to work together on larger collaborative endeavours (shelter and boat building) and divide safely into sub-groups for specific tasks (hunting, fishing, gathering wood etc) but not so many that cliques and divisions begin the form.

For the Invercauld, maybe starting with nineteen, coupled with inadequate leadership, sealed their fate from day one?

Remember, this was 1864. This type of collaborative leadership, consciously created or not, would have been radical at the time; for the crew of the Grafton to reject previous social norms and create new ways of working together was a truly remarkable and audacious act.

Ultimately it is all about leadership

Of course, it’s not every day we face being shipwrecked, but my point is that right now, our business and social context (the external environment that impacts on us) is changing at an unprecedented rate.

Just as storms radically changed the context for the Grafton and the Invercauld, so it is with us.

It is our enduring leadership response to that relentless storm that matters.

So if we were to review how the crew of the Grafton faired, through the modern lens of Collaborative Leadership, what can we learn?

- They had a clear North Star – nobody was going to rescue them, they were going to have to do this themselves, even if it was perilous and uncertain.

- They flattened the hierarchy – created a new social structure based on discussion and consensus; they elected a leader based on pragmatism, not ego.

- They created rituals – they gathered every Sunday and read out their rules of community; decision-making was fair and transparent; this was how they were going to survive together.

- They reminded themselves of what mattered – they set out their ways of working and what they were striving hard to achieve; it was more than survival, it was bold self-rescue.

- They recognised that conflict was inevitable – stress, fear, hunger, cold and isolation drive powerful emotions and behaviours; they held regular gatherings to surface and defuse tension.

- They shared resources – the precious food and resources they brought ashore belonged to the owner, Raynal and his captain, Musgrave and yet were immediately stored and shared communally – a clear signal that they were in this together from the start.

- They leveraged their skills – they hunted seals, they fished, they built a furnace, they fashioned a ocean-going raft; each task taken, based on experience and aptitude rather than comfort, safety or status.

- They were solution-oriented – even in the hardest times, they knew they couldn’t allow despair to take hold; focus on the North Star and work towards small daily wins.

- They created tangible sub-steps – find food, build a shelter, build a furnace, make nails; clear, measurable tasks and outcomes that build towards the desired outcome.

- They were bonded – these five sailors had a remarkable and fortunate mix of emotional intelligence, shared leadership and a drive to survive; their lack of ego and incredible courage, combined with empathy and grit is testament to the strength of collaborative leadership.

I hope that in their own way, forged in those most extreme circumstances, the brave crew of the Grafton: Thomas Musgrave, François Raynal, George Harris, Alexander “Alick” Maclaren and Henry Forgès might also have recognised this Collaborative Leadership in themselves.

When you want to find out more about the work we are doing all over the world, building outstanding leadership cultures and collaborative, high performance teams, please do get in touch.

We are ready when you are.