What connects three sibling chess champions, the world’s largest car manufacturer and a device known as the Blue Box?

And what can they tell us about contemporary approaches to leadership development?

In the 1970’s, László and Klara Polgár deliberately and successfully set out to build each of their three daughters into world chess champions.

In 1986 the Toyota Motor Company adopted kaizen as a deliberate approach to quality improvement, setting it on course to become the world’s largest car company.

Fifty-nine years earlier, Edwin Link invented the first flight simulator, the Link Blue Box Trainer, accelerating pilot competency, saving countless lives and many hours of expensive and resource-intensive training flights.

Nowadays, we wouldn’t dream of putting a pilot, astronaut, soldier, surgeon or deep sea diver out in the field without many hours of simulated, deliberate rehearsal.

And yet, for so many leaders in business, development starts way too late, is haphazard, sporadic, or worse, seen as a crutch for those who aren’t “natural leaders”.

We need to challenge this leadership myth; treat executive development seriously and start getting deliberate about leadership.

The myth of the “natural leader”

First of all, let’s consider where the problem might have started: Thomas Carlyle and the myth of the “natural leader“.

Thomas Carlyle was a Scottish historian and writer in the 1800’s, struggling to make sense of the Napoleonic Wars raging across Europe.

His popular, and catchily-titled book of the time, “On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History”, set out his “Great Man Theory”; an extended argument that history has been shaped by a series of heroic, Y chromosone-bearing individuals. These men, usually warrior leaders, (think Alexander the Great, Napoleon, Oliver Cromwell, Julius Caesar, Abraham Lincoln etc) rose from relative obscurity to lead their people to prosperity and it was their natural, innate leadership that made it all possible.

“No great man lives in vain. The history of the world is but the biography of great men.”

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 1795 – 5 February 1881)

The shortcomings of the Great Man Theory are huge.

It lacks any scientific validity, only considers men in power, emphasises personal characteristics such as height and physical appearance, doesn’t define what “great” means, suffers from survivor bias and relies almost completely on social context. If your starting point is that aristocratic power is god-given and leadership characteristics are granted at birth, then it doesn’t leave much leadership room for the rest of us.

But the popularity of his writing at the time leads directly to Hierarchical Dependancy, a Leadership Loophole legacy that we are still struggling with today.

It has embedded a certain leadership mindset that is not fit for modern purpose: it maintains the macho myth – be heroic, be certain, be powerful, know it all, decide it all.

The allure of “hero” is still very much with us – you can’t go to the cinema these days without being surrounded by superheroes – and it is undoubtedly tempting. It lets the rest of us off the responsibility hook; leadership is for the few, the gifted, the charismatic.

It’s an unsustainable and unrealistic approach to contemporary business leadership.

Getting deliberate about excellence

If we turn away from Thomas Carlyle, what option do we have instead?

The research suggests that the answer lies in being deliberate.

Raising a chess champion, or three…

The Hungarian educational psychologist, László Polgár and his wife, Klara, who was a teacher, didn’t just hope that their children were going to be successful; they deliberately set out to make it happen, before they were even born. Boy or girl, each child would be built into a grandmaster chess player.

Their controversial real world experiment was rooted in his book, Raise a Genius! (Nevelj zsenit!), where László set out his central argument that “genius equals work and fortunate circumstances… geniuses are made, not born”.

And the practical application of his bold premise: “that any child has the innate capacity to become a genius in any chosen field, as long as education starts before their third birthday and they begin to specialise at six” resulted in something remarkable.

Of their three daughters, the least successful (in chess terms) became the sixth-best woman chess player in the world, the middle sibling was the world’s highest-ranked female chess player for nearly twenty years and the third sister was right behind her as the second-best female chess player in the world at the age of seventeen.

Radical conformity in car manufacture

On the other side of the world and four decades ago, the Toyota Motor Company was a middle-sized car company. Today, it’s the world’s largest car manufacturer, measured by global sales. The astonishing rise of Toyota is in part due to its famous Toyota Production System and the deliberate practice of kaizen (continuous improvement).

“It’s estimated that each year Toyota implements around a thousand fixes in each of its assembly lines, resulting in about a million tiny fixes overall.”

Toyota UK Magazine

Now widespread, kaizen was, at the time, a radical philosophy of deliberate, distributed responsibility: a culture where every employee is purposefully seeking out and identifying small problems to fix.

Learning to fly without leaving the ground

When the basic training cost of an F-22 fighter pilot is $10.9 million, the plane itself costs $350 million and the flying cost of your plane is $85,325/hour, you want to be pretty deliberate about your skill acquisition.

Flight simulators are by far the cheapest (relatively speaking) and certainly most effective way of training pilots. Scenarios can be tested, rehearsals performed without consequence and drills repeated until perfect. It is now difficult to imagine any pilot not using a simulator to assess, test and hone their skills.

And yet, they were originally treated with scepticism by the military and Edwin Link’s first flight simulator was most usually found in fairgrounds. It wasn’t until twelve pilots of the US Air Mail were killed over a 78-day period in 1933-34 that the US Army Air Corps started to look seriously at improving pilot training.

With an initial order for just six of his Link Blue Box Trainers, the US military began to deliberately test and stretch their pilots so they could fly with instruments only, making them better and safer pilots, at a pace that was previously impossible.

“The Luftwaffe met its Waterloo on all the training fields of the free world where there was a battery of Link Trainers”

Air Marshall Robert Leckie (wartime RAF Chief of Staff)

During World War 2, more than half a million US pilots had been trained on Edwin Link’s flight simulators; incredible machines of pumps, bellows and valves that cost as little as $3,500 to buy, and that saved thousands of lives.

So what are we to take from these stories?

I think the first thing to consider is that we are so easily seduced by the myth of the talented, the gifted, the natural.

And whilst clearly some people have a pre-disposition towards certain sports, an ability to paint, to compose music etc, the secret sauce here isn’t innate talent; it is a complex combination of passion, focus, context and a lot of hard work.

Not just any old hard work but structured, deliberate hard work.

Developing Grit

The psychologist and academic, Angela Duckworth talks about grit: an unflinching commitment to complete what you start, to bounce back, to get better, and to practice, practice, practice.

What she calls “grit paragons”, whether they be swimmers, chefs, army cadets or telesales executives, have a common focus on an ”ultimate concern” – a goal you care about so much that it organises and gives meaning to almost everything you do.

“Gritty people train at the edge of their comfort zone. They zero in on one narrow aspect of their performance and set a stretch goal to improve it.”

Angela Duckworth, professor of psychology, University of Pennsylvania

So when I said “practice, practice, practice”, that isn’t the whole picture; it is a bit more subtle than that.

There is a common idea, popularised by Malcom Gladwell, that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to build an expertise; but on closer inspection, what really matters most is the quality of that practice.

After all, investing so much time practicing the wrong things is never going to help.

Focussing on Deliberate Practice

K. Anders Ericsson was a Swedish psychologist who spent more than thirty years studying how we acquire expertise, particularly in athletics, but also in music and business.

His concept of Deliberate Practice encompasses “the individualised training activities specially designed by a coach or teacher to improve specific aspects of an individual’s performance through repetition and successive refinement” (Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996, pp. 278–279) with a very clear focus on skill stretch, structured rehearsal, sustained effort, and accurate, timely feedback.

“Excellence demands effort and planned, deliberate practice of increasing difficulty.”

K. Anders Ericsson (1947 – 2020)

As Aubrey Daniels, the psychologist and originator of Performance Management puts it:

“Consider the activity of two basketball players practicing free throws for one hour.

Player A shoots 200 practice shots, Player B shoots 50. The Player B retrieves his own shots, dribbles leisurely and takes several breaks to talk to friends. Player A has a colleague who retrieves the ball after each attempt. The colleague keeps a record of shots made. If the shot is missed the colleague records whether the miss was short, long, left or right and the shooter reviews the results after every 10 minutes of practice.

To characterise their hour of practice as equal would hardly be accurate. Assuming this is typical of their practice routine and they are equally skilled at the start, which would you predict would be the better shooter after only 100 hours of practice?”

Both players A and B could rightly say they practiced for an hour, but only one of them practiced deliberately.

Six Markers of Deliberate Practice

- Curiosity – an insatiable desire to improve, to question everything and to learn from the best. Always be looking outside for fresh ideas and marginal gain.

- Purpose – a tangible, measurable goal that will take effort to achieve. What Jim Collins would call a BHAG (big hairy audacious goal).

- Stretch – understanding your skill threshold and your comfort zone and then consistently pushing at them with structured practice over time – a lot of time.

- Chunking – breaking behaviours and complex tasks, routines or manoeuvres into smaller, more manageable drills.

- Consistency – turning up early and doing your best, every day. It doesn’t have to be perfect and sometimes it will be worse before it is better but consistency is commitment to a purpose.

- Accurate Feedback – asking for, and expecting, real time, actionable feedback from multiple sources. You don’t have to act on everything but you are looking for patterns and fresh insights – especially when the observations are uncomfortable.

How does being deliberate relate to leadership?

If we are to move away from the toxic and unhelpful legacy of the Great Man Theory, then we need to get serious about how we approach leadership.

In the context of modern business, we need to see leadership as a behavioural skillset, a craft to be honed over time, with support, challenge and focus. For us to experience effective leadership throughout our organisations, from cleaner to CEO, we need to have a fresh and deliberate approach – it will not happen by accident or by recruiting a few shining stars.

“Natural talent and intellect come second to perseverance and a willingness to adapt and learn from your mistakes and failures.

A determined spirit always wins out over unfocused genius.”

Beau Taplin (writer) – Natural Talent

Not all of us will have the energy, passion or focus that it takes. And that’s OK.

There is a reason why only a few of us ever become elite athletes, fighter pilots or world chess champions. We don’t have the initial spark, or the grit and determination to keep pushing, or we are just not prepared to make the necessary sacrifices.

And that really is OK.

But let’s set the bar and consider how we create a deliberate leadership context.

Ten Deliberate Leadership Actions

Building a context of Deliberate Leadership is a conscious act. You can decide, with those around you, to make this happen, or not.

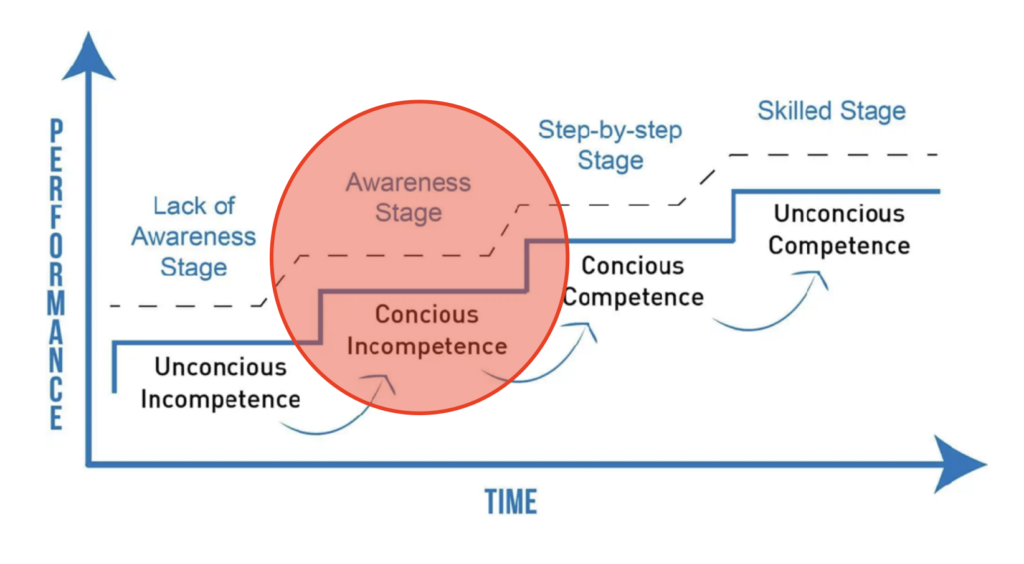

It won’t cost you money and you don’t need permission but it will take effort. Before you even start thinking about the 10,000 hours, you have to overcome what the writer Josh Kaufman calls the “frustration barrier”; a period of irritating “conscious incompetence”. You are painfully aware of not being great at the new behaviours you are trialling and the temptation to revert back to the familiar ones looms large, so you must commit to sticking with them for at least twenty hours of practice.

For experienced leaders it is even harder; the act of deliberately unlearning previously useful behaviours feels insurmountable. The short term implications for ego, reputation and self-image can make some fall at the first hurdle.

So, if you are ready for Deliberate Leadership, to work regularly on the leadership behaviours you want to show, and to do it with intention and specific goals in mind, here are ten leadership actions:

1. IDENTIFY YOUR NORTH STAR

Decide on your guiding principles and values; your North Star is a consistent and reliable guide for your decision-making, vision-sharing and direction of travel, both individually and as an organisation. It will be tested, so it needs to be robust and of meaningful value; it will come into its own when the journey get rough.

This is your “why”.

2. CRAFT YOUR LEADERSHIP SIGNATURE

Your signature is as unique as you are. And your leadership needs a signature. Your reputation, your ways of working, your distinct leadership style; inspiring, comforting and challenging those around you. The test of a leadership signature is that those around you could describe it back to you without prompting.

This is your “how”.

3. PUBLISH YOUR LEADERSHIP MANIFESTO

Write a manifesto that sets out clearly what you believe will make a positive difference to the context for those around you. It is an opportunity to literally make your leadership manifest – obvious, clear and open for debate. A manifesto is a campaigning document, a rallying cry for a better future, a fresh vision with a strategy and story.

This is your “what”.

4. ADOPT A GROWTH MINDSET

When you adopt a Growth Mindset, (Carole Dweck, 2015) your attitude becomes one of curiosity, exploration, continual learning and resilience. Your abilities can be developed by applying effort and hard work to the task – any brains and talent that you have are just your ticket to the game.

5. CHUNK DOWN THE TOUGH STUFF

Break any complex or new leadership behaviour into its component parts and work out how to build familiarity and comfort in the drills of smaller, manageable tasks. Prepare, rehearse, test and experiment in safe environments before combining with other drills to create more complex leadership routines.

Chunk down board presentations, feedback conversations, strategy deployments, leading change – whatever it is that needs your conscious, deliberate leadership.

6. LEAN INTO THE BEHAVIOURAL STRETCH

Look for the moment of leadership discomfort and push on anyway. Test the boundaries and explore the edges of your leadership – your decision-making, your approach to conflict, your creativity – whatever it may be. Decide what you want to get better at, how that is going to happen and who is best placed to help you.

7. SHARE GENEROUSLY

You are not alone on this journey and Deliberate Leadership is a shared act. Be generous with your time, ideas and experiences to help others on their leadership journeys. You are a lighthouse for others – a beacon of safety and guidance, helping others avoid the sharp rocks of your mistakes and guiding them to safe havens in the storm.

Be a mentor; don’t be afraid to ask for help and be the first to offer it.

8. CREATE A FEEDBACK CULTURE

Foster an expectation of high quality performance feedback as a route into conversations about intention, impact and reputation. The further you progress up the corporate ladder, the harder it is to get honest feedback, as Shakespeare’s Henry V said when obliged to visit his soldiers in disguise, in order to understood how they felt on the eve of battle, “I think the king is but a man, as I am: the violet smells to him as it doth to me.”

9. DEVELOP STAMINA

Deliberate Leadership is a marathon not a sprint; it takes time, patience, practice and a steely resolution. For those who really commit, this journey will not be over any time soon, so pace yourself and settle into a leadership rhythm that is stretching but sustainable.

10. EMBRACE SELF CARE

In and amongst all this talk of leadership development, focus and stretch, it is easy to lose sight of yourself. Performers at the top of their game, whether they are athletes, pilots or surgeons know the value of self care – looking after the whole self in order to perform better in the long term. Proper selfishness is entirely acceptable – eat properly, sleep well, have fun, laugh often and loudly – because deliberate leadership is a whole person activity.

When you want to find out more about the work we are doing with teams and organisations all over the world, developing deliberate leaders, do get in touch.

We are ready when you are.