What connects an affordable but dangerous car, a fizzy drink and a mobile phone?

The answer is wrapped up in a fog of corporate mis-management and a failure to navigate the leadership challenges of dilemma, paradox and ambiguity.

In our VUCA reality, leaders are gradually (and sometimes grudgingly) coming to terms with not knowing. They are starting to build models of leadership based on other fields of expertise: collaborative exploration, iterative experimentation, risk/reward balancing.

The leadership edge here is in understanding the distinct nature of your uncertainty: dilemma, paradox or ambiguity, and adopting an appropriate approach, engaging others in the solution-seeking and demonstrating clarity in your decision-making.

So let’s start with some definitions:

Dilemma – a choice between equally undesirable options, each with its own set of consequences, for example, the tension between short-term profitability and long-term sustainability.

Paradox – situations where seemingly contradictory elements co-exist, challenging our conventional thinking and decision-making. The paradox of stability and change in organisations is that we have to change, even if the objective is to stay the same, because the context around us makes it so.

Ambiguity – events characterised by a lack of clarity or certainty, with incomplete or conflicting information making it difficult to discern the appropriate course of action.

Now we have that out of the way, let’s look at an infamous, high profile example of each:

DILEMMA

The Ford Pinto Scandal: safety versus profitability

In the late 1960s, Ford Motor Company developed the Ford Pinto, a compact car aimed at competing with foreign imports into the American market. However, during the design phase, engineers discovered a significant safety flaw: the positioning of the fuel tank made the car susceptible to rupturing and catching fire in rear-end collisions at relatively low speeds.

Ford executives were faced with a critical decision (the dilemma): should they address the safety issue, which would involve redesign, time and substantial costs, or proceed with production to meet aggressive launch deadlines and maintain profitability?

The infamous “Pinto Memo” which was leaked to the press at the time, suggests that Ford’s leadership decided to prioritise cost-effectiveness over safety. Executives calculated that the cost of recalling the Pinto would have been $121 million, whereas paying off the victims would only have cost Ford $50 million. Assessing the value of a life at $200,000 and serious injury at $67, 000, between 1971 and 1978, the Pinto’s lethally poor design was responsible for a number of fire-related deaths and Ford was finally obliged to recall all 1971-76 Pintos for fuel-tank modifications in 1978.

This dreadful Pinto tale is a classic corporate dilemma: two undesirable options (from the perspective of Ford leadership), costly product safety, consumer welfare (long term, abstract), over financial gains and market protection (short term, quantifiable). Ultimately, the fallout from the Pinto Scandal prompted reforms in product safety regulations and business ethics, which is obviously a good thing, whilst providing a painful corporate lesson.

PARADOX

The New Coke Fiasco: change but don’t change

In the mid-1980s, Coca-Cola faced intense competition from its bitter rival, Pepsi, who had been gradually gaining market share. With a sweeter taste and aggressive marketing, Coca-Cola was beginning to feel the pinch.

In a bold move, Coca-Cola’s leadership decided to reformulate their flagship product and introduced the world to “New Coke.” The revitalised formula copied the sweeter taste of Pepsi and yet was met with outrage, shock and panic-buying from loyal Coke drinkers.

The paradox lies here: their decision was based on extensive market research and taste tests, indicating a clear preference for the sweeter flavour. But the company failed to anticipate the visceral emotional attachment that consumers had to the original.

“I think, by the end of their nightmare, they figured out who they really are. Caretakers. They can’t change the taste of their flagship brand. They can’t change its imagery. All they can do is defend the heritage they nearly abandoned in 1985.”

Pepsi-Cola USA’s CEO Roger Enrico

Recognising the existential threat to its brand reputation, on July 11, 1985, after only 77 days, the previous version of Coke was brought back as “Coca-Cola Classic” in what was referred to as “the biggest marketing blunder of all time.”

So what does this example tell us? That consumers (us) are capable of holding two contrary opinions at the same time – we want a sweeter drink, but don’t want change. And this experience reflects the wider paradoxical nature of business decisions, where actions intended to drive growth and adaptation result in unintended and unpredictable consequences.

AMBIGUITY

The Decline of Nokia: don’t fear the fruit company from California

In 2007, Nokia had 51% market share of the mobile phone market, was valued at $300bn, and represented 70% of Helsinki’s stock exchange market capital. Just 9 short years later, when Microsoft (who owned it by that point), sold it in 2016, it realised only £350m.

So why the rapid fall? In part, it was Nokia’s ambiguity in response to unlikely threat. In the early 2000s, Nokia was the dominant force in the mobile phone industry; renowned for durable and user-friendly devices.

Everything changed in 2007 with the launch of the iPhone, introducing the world to engaging touch-screen technology. Despite cries from senior Nokia leaders to “not be afraid of the fruit company from Cupertino” the writing was on the wall. Nokia faced a critical decision: whether to maintain its focus on traditional mobile phones or to pivot towards smartphones. In the face of challenge, it decided to do – nothing.

Sitting on a healthy pile of cash and a dominant market share, with a supply chain and logistics infrastructure to match, making 13 phones a second, it is perhaps easy to see why arrogance, hubris and complacency led to a culture of lazy ambiguity.

Here were the “ambiguity challenges” for Nokia:

- Market Trends vs. Core Competencies: ambiguity within Nokia’s leadership about whether to deviate from its core competencies and invest heavily in developing smartphones, which represented a significant departure from its established product lineup, even though the tech was sitting in its research labs.

- Competitive Landscape vs. Innovation: Nokia stumbled over how to remain competitive – they were an engineering-led company making bomb-proof, durable tech; the iPhone was a consumer-driven plaything. There was fundamental disagreement within Nokia’s leadership about whether the smartphone trend would be a passing fad or a long-term disruption.

- Global Strategy vs. Local Adaptation: Nokia faced challenges in navigating diverse consumer preferences (dual-SIM phones were a big deal in South East Asia but irrelevant in Europe) and market dynamics across different regions, leading to ambiguity about the most effective strategy for addressing the varying needs of customers worldwide.

Nokia’s response to the rise of smartphones is a tale of half-hearted ambiguity and leadership indecision. After initially adopting a reticent approach to touchscreen technology, they struggled to accept a “smartphone future” and failed to formulate a clear and cohesive strategy for transitioning away from their ego-attachment with feature phones.

Ultimately, their lack of decisive action proved costly, as the company lost market share to competitors who were swarming all over the smartphone revolution.

Nokia paid the price for leadership arrogance, poor situational awareness and lame decision-making in the face of such disruptive technological change. The company’s reluctance to fully embrace smartphones and pivot its heavily invested strategy proved to be its downfall.

VUCA, BANI and the fog of not knowing

The VUCA environment that we are all in, first described by Bennis & Nanus in 1985, just amplifies the complexities associated with dilemma, paradox and ambiguity, exacerbating already significant challenges for leaders:

- Volatility demands adaptability and agility to respond to sudden changes in the market or operating conditions.

- Uncertainty requires leaders to make decisions with imperfect information, navigating uncharted territories.

- Complexity entails understanding interconnected systems and addressing multifaceted issues that defy straightforward solutions.

- Ambiguity necessitates tolerance for uncertainty and the ability to find a path forward, becoming comfortable with the discomfort.

Following on from VUCA, the BANI framework, introduced by Jamais Cascio in 2016, takes an enhanced view, offering additional insights into the daunting realities of leading in the modern business context:

- Brittle: Traditional structures and strategies may prove ineffective in the face of rapid change and disruption.

- Anxious: Uncertainty breeds anxiety, making it difficult for leaders to make confident decisions.

- Nonlinear: Linear cause-and-effect relationships may no longer hold true in complex adaptive systems.

- Incomprehensible: The sheer volume and complexity of information make it challenging to discern patterns and make sense of the world.

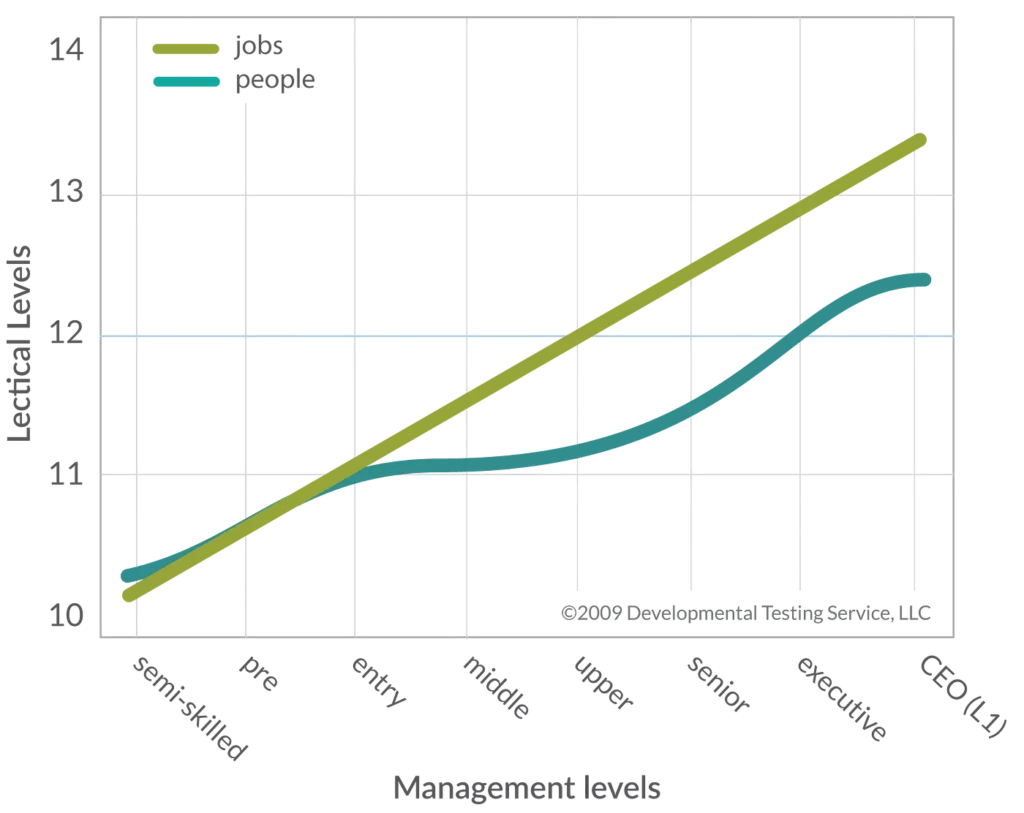

The advent of new technologies and opportunities is not going to make this any easier; indeed quite the opposite. From a leadership perspective, we are going to see a paradigm shift in what it means to be successful. The “complexity gap” articulated by Theo Dawson makes it clear that traditional “command and control” leadership mindsets are no longer sustainable. It is proving impossible to make reliable decisions, that have far-reaching and often unintended consequences, in a highly centralised manner – the variables and unknowns are too great and shifting too fast.

If we are going to face into this “fog of not knowing” then we need to do it together, in a more collaborative, humble way, filling in the gaps, looking out for each other and listening more intently to diverse voices.

In practice, this means we need to acknowledge our individual limitations (which might be the toughest ask of all) and actively work on developing new skills, behaviours and knowledge. We need to work closely with, and actively seek out, difference whilst building and embedding systems and processes that help us understand different perspectives quickly and get to the essence of the issue, often holding two or more contrary positions at the same time!

What do we need to get better at?

So what leadership qualities do we need to enhance if we are going to thrive in a world of increased dilemma, paradox and ambiguity? Here are four areas of focus for your deliberate leadership practice:

- Adaptive Leadership emphasises flexibility and resilience in addressing complex challenges. Instead of relying on predefined solutions, adaptive leaders foster a culture of learning and experimentation, encouraging flexible responses to changing circumstances. They embrace uncertainty as an opportunity for growth and innovation, continuously adapting their strategies in response to evolving conditions.

- Systems Thinking enables leaders to understand the interconnectedness of variables within complex systems. By adopting a holistic perspective, leaders can identify leverage points and anticipate unintended consequences, facilitating more effective decision-making. They recognise that organisations are dynamic systems, influenced by internal and external factors, and strive to optimise the system as a whole rather than focusing solely on individual components.

- Authentic Leadership focusses on self-awareness, transparency, and integrity; building trust through genuine relationships, fostering open communication and engagement. Those who emphasise their authenticity lead by example, staying true to their values and principles, and empower others to do the same.

- Collaborative Leadership requires an approach that is attuned to the external context and the needs of the team and organisation; it challenges the value drain of the Leadership Loopholes, moving from authoritarian parent-child to mature, adult-adult relationships. There are six key tenets of collaborative leadership: a clear North Star, valuing diverse perspectives, community bonding, broad spectrum communication, robust challenge and a solution-orientation.

How does leadership decision-making need to flex?

Dilemma, paradox and ambiguity are distinct entities and not only need to be recognised but then also approached differently. Your leadership decision-making process must flex significantly depending on which you are dealing with. Here’s how they might differ:

Dilemma

Identify Conflicting Objectives: when faced with dilemma, first identify the conflicting objectives or choices at hand. This involves understanding the trade-offs involved in each option and the potential consequences for stakeholders.

Balance Stakeholder Interests: be rigorous and equitable in considering the needs and interests of stakeholders (customers, employees, shareholders, and the broader community). Acknowledging, fully understanding and challenging your biases about these competing interests is crucial in finding a satisfactory resolution.

Evaluate Short-term versus Long-term Impact: assess immediate benefits compared to long-term implications. We tend to have a positive bias towards short term, tangible actions compared to long term, abstract outcomes so we need to clearly articulate and consider the broader strategic goals and values of the organisation.

Paradox

Embrace Contradictory Forces: acknowledge the reality of contradictory data or viewpoints simultaneously. Recognise that opposing ideas or strategies can co-exist and may even be interdependent.

Promote Creativity and Innovation: foster a culture of creativity and innovation; encourage divergent thinking and experimentation. Even with teams who don’t see themselves as creative, emphasise curiosity and lateral thinking to explore “what if?” solutions that transcend conventional dichotomies.

Navigate Complexity and Uncertainty: expand your psychological bandwidth for variance and iteration, even pausing process if need be. Decisions need to be re-visited on a regular basis to ensure the contextual conditions are still valid and the decision criteria are solid in light of emerging and potentially conflicting perspectives.

Ambiguity

Tolerate Uncertainty: develop an acceptance for uncertainty and ambiguity, it is rarely going to 100% so be OK with 80%. Accept that complete information may not be available and that decisions may need to be made based on incomplete or contradictory data. Be clear about the process, rationale and decision; own the outcome.

Encourage Learning and Exploration: foster a willingness in your team to learn and explore alternative paths. Encourage outside perspectives, experimentation, and continuous learning to uncover new insights and opportunities.

Facilitate Collaboration and Adaptation: ambiguity is best addressed through collaborative decision-making. Leverage diverse perspectives and expertise; give teams the space to iterate and adjust approaches based on emerging information and changing circumstances.

What clarity can leaders work on?

In the face of dilemma, paradox and ambiguity, the leader’s role is to provide context, encouragement and direction in the fog. It isn’t easy and requires humility and vulnerability but there are four clarities that you can provide for those around you:

- Strategic Clarity – a clear North Star; a confidently articulated vision and purpose that you refer to continuously and share widely. Use your North Star to clarify decisions, priorities and strategic emphasis.

- Behavioural Clarity – work hard to build and embed an agreed set of behaviours in your team. Consider how you support the behaviours and how you challenge contrary action; develop the positive rituals that will build confidence, comfort and courage in the face of uncertainty.

- Communication Clarity – clear, consistent messaging, using simple language is key. Minimise acronyms, jargon and phrases that can alienate those who are less familiar or central. Don’t be afraid to repeat, repeat, repeat! Ask for summaries to check understanding, listen out for assumptions and filtered, selective hearing in your team.

- Expectation Clarity – what have we agreed and who is responsible for what? What standards and time frames have we agreed to? How do we ensure that we meet our commitments and what are the consequences if we don’t? These are the tough leadership questions that build ownership and accountability in the fog.

When you want to find out more about the work we are doing with teams and organisations all over the world, helping create leadership clarity, do get in touch.

We are ready when you are.